What basic assumption about the environment did opponents to environmental regulation have?

Our growing population

We humans are remarkable creatures. From our humble beginnings in small pockets of Africa, we have evolved over millennia to colonise about every corner of our planet. We are clever, resilient and adjustable―perhaps a little as well adaptable.

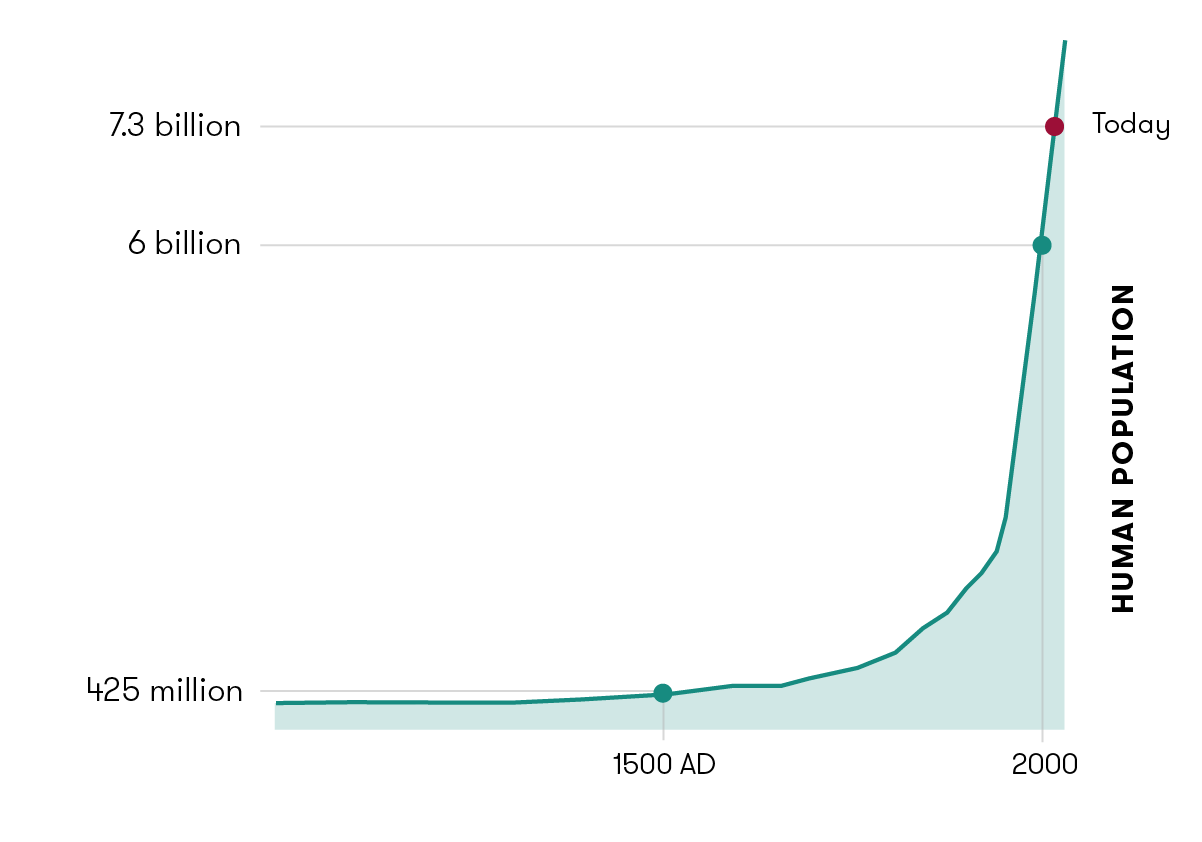

In 2015 the world population is more than 7.3 billion people. That's more than seven billion iii hundred million bodies that need to be fed, clothed, kept warm and ideally, nurtured and educated. More than 7.3 billion individuals who, while busy consuming resource, are likewise producing vast quantities of waste, and our numbers go along to grow. The Un estimates that the world population will achieve ix.2 billion by 2050.

For most of our being the human population has grown very slowly, kept in check past disease, climate fluctuations and other social factors. It took until 1804 for the states to reach 1 billion people. Since then, standing improvements in nutrition, medicine and engineering have seen our population increase quickly.

The impact of and then many humans on the environment takes two major forms:

- consumption of resources such as state, nutrient, h2o, air, fossil fuels and minerals

- waste products as a result of consumption such equally air and water pollutants, toxic materials and greenhouse gases

More than than simply numbers

Many people worry that unchecked population growth will eventually crusade an environmental catastrophe. This is an understandable fear, and a quick look at the circumstantial testify certainly shows that equally our population has increased, the health of our environment has decreased. The touch on of and so many people on the planet has resulted in some scientists coining a new term to describe our time—the Anthropocene epoch. Dissimilar previous geological epochs, where various geological and climate processes defined the time periods, the proposed Anthropecene period is named for the dominant influence humans and their activities are having on the surroundings. In essence, humans are a new global geophysical strength.

However, while population size is office of the trouble, the issue is bigger and more complex than just counting bodies.

There are many factors at play. Essentially, information technology is what is happening inside those populations—their distribution (density, migration patterns and urbanisation), their limerick (historic period, sex and income levels) and, most chiefly, their consumption patterns—that are of equal, if not more than importance, than just numbers.

Focusing solely on population number obscures the multifaceted relationship betwixt u.s.a. humans and our environment, and makes it easier for u.s. to lay the blame at the feet of others, such as those in developing countries, rather than looking at how our own behaviour may be negatively affecting the planet.

Let's accept a closer await at the bug.

Population size

It'due south no surprise that as the globe population continues to grow, the limits of essential global resources such as drinkable water, fertile land, forests and fisheries are condign more obvious. You don't have to be a maths whizz to work out that, on the whole, more people utilise more resources and create more waste material.

But how many people is as well many? How many of us can Globe realistically support?

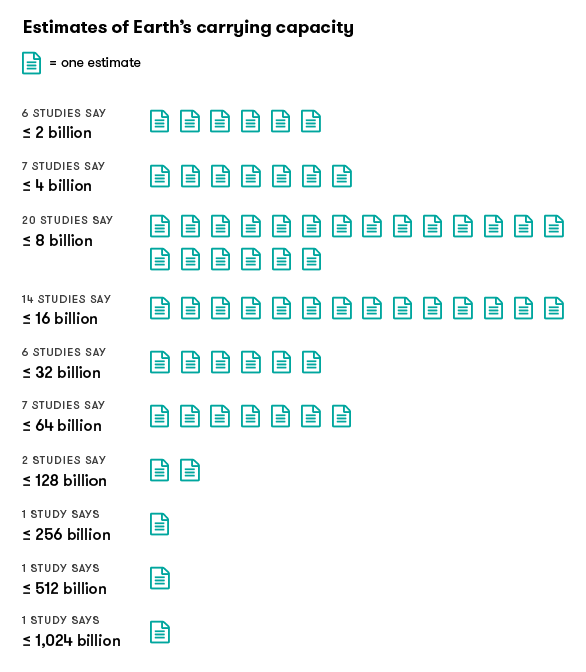

Influenced by the work of Thomas Malthus, ' carrying capacity ' can be divers equally the maximum population size an surroundings tin sustain indefinitely.

Debate almost the actual man carrying capacity of Earth dates back hundreds of years. The range of estimates is enormous, fluctuating from 500 million people to more than 1 trillion. Scientists disagree not only on the final number, just more importantly about the best and most accurate style of determining that number—hence the huge variability.

How can this be? Whether we accept 500 million people or one trillion, we all the same have only one planet, which has a finite level of resources. The answer comes back to resource consumption. People around the earth consume resources differently and unevenly. An average centre-form American consumes three.3 times the subsistence level of nutrient and almost 250 times the subsistence level of make clean h2o. So if everyone on Earth lived like a middle class American, then the planet might have a carrying capacity of effectually 2 billion. However, if people only consumed what they actually needed, then the Earth could potentially back up a much higher figure.

Simply we demand to consider not but quantity but also quality—Globe might be able to theoretically support over i trillion people, just what would their quality of life be like? Would they be scraping by on the bare minimum of allocated resources, or would they take the opportunity to lead an enjoyable and total life?

More importantly, could these trillion people cooperate on the scale required, or might some groups seek to use a disproportionate fraction of resources? If so, might other groups claiming that inequality, including through the employ of violence?

These are questions that are yet to be answered.

Population distribution

The ways in which populations are spread across Earth has an event on the surroundings. Developing countries tend to have college birth rates due to poverty and lower access to family planning and education, while developed countries have lower nascency rates. In 2015, eighty per cent of the world'south population alive in less-developed nations. These faster-growing populations can add together pressure level to local environments.

Globally, in almost every country, humans are also condign more than urbanised. In 1960 less than i 3rd of the earth's population lived in cities. By 2014, that effigy was 54 per cent, with a projected ascension to 66 per cent by 2050.

While many enthusiasts for centralisation and urbanisation fence this allows for resources to be used more efficiently, in developing countries this mass movement of people heading towards the cities in search of employment and opportunity oft outstrips the pace of development, leading to slums, poor (if whatever) environmental regulation, and higher levels of centralised pollution. Even in developed nations, more people are moving to the cities than ever before. The pressure placed on growing cities and their resources such as water, energy and food due to standing growth includes pollution from additional cars, heaters and other modern luxuries, which can cause a range of localised environmental problems.

Humans have always moved effectually the world. However, authorities policies, conflict or environmental crises can enhance these migrations, often causing curt or long-term environmental impairment. For instance, since 2011 conditions in the Heart Due east have seen population transfer (likewise known equally unplanned migration) result in several million refugees fleeing countries including Syria, Iraq and Transitional islamic state of afghanistan. The sudden development of often huge refugee camps can affect water supplies, cause land damage (such as felling of trees for fuel) or pollute environments (lack of sewerage systems).

Population limerick

The composition of a population can also affect the surrounding environment. At nowadays, the global population has both the largest proportion of immature people (under 24) and the largest percentage of elderly people in history. Equally young people are more than likely to migrate, this leads to intensified urban environmental concerns, as listed above.

Life expectancy has increased by approximately 20 years since 1960. While this is a triumph for mankind, and certainly a good matter for the individual, from the planet's point of view it is just another body that is continuing to eat resource and produce waste material for around 40 per cent longer than in the past.

Ageing populations are another chemical element to the multi-faceted implications of demographic population change, and pose challenges of their own. For example between 1970 and 2006, Nippon's proportion of people over 65 grew from 7 per cent to more 20 per cent of its population. This has huge implications on the workforce, every bit well equally authorities spending on pensions and health care.

Population income is also an important consideration. The uneven distribution of income results in pressure on the environment from both the everyman and highest income levels. In order to simply survive, many of the world's poorest people partake in unsustainable levels of resource utilise, for example burning rubbish, tyres or plastics for fuel. They may besides be forced to deplete deficient natural resource, such as forests or animal populations, to feed their families. On the other end of the spectrum, those with the highest incomes consume unduly big levels of resources through the cars they drive, the homes they live in and the lifestyle choices they brand.

On a country-wide level, economic development and environmental damage are also linked. The to the lowest degree developed nations tend to have lower levels of industrial activeness, resulting in lower levels of environmental damage. The most developed countries have found ways of improving technology and free energy efficiency to reduce their environmental impact while retaining high levels of production. It is the countries in between—those that are developing and experiencing intense resource consumption (which may exist driven by demand from developed countries)—that are often the location of the most environmental damage.

Population consumption

While poverty and environmental degradation are closely interrelated, it is the unsustainable patterns of consumption and production, primarily in developed nations, that are of even greater concern.

Information technology'south not ofttimes that those in developed countries terminate and consider our own levels of consumption. For many, particularly in industrialised countries, the consumption of appurtenances and resource is just a office of our lives and culture, promoted not only past advertisers but also by governments wanting to continually grow their economy. Culturally, it is considered a normal part of life to shop, purchase and eat, to continually strive to own a bigger habitation or a faster automobile, all ofttimes promoted equally signs of success. It may be fine to participate in consumer culture and to value material possessions, but in backlog it is harming both the planet and our emotional wellbeing.

The ecology touch of all this consumption is huge. The mass production of goods, many of them unnecessary for a comfortable life, is using large amounts of energy, creating excess pollution, and generating huge amounts of waste.

To complicate matters, environmental impacts of loftier levels of consumption are not confined to the local area or fifty-fifty country. For case, the use of fossil fuels for energy (to drive our bigger cars, oestrus and cool our bigger houses) has an impact on global COtwo levels and resulting ecology effects. Similarly, richer countries are besides able to rely on resources and/or waste material-intensive imports being produced in poorer countries. This enables them to savor the products without having to deal with the immediate impacts of the factories or pollution that went in to creating them.

On a global scale, not all humans are every bit responsible for environmental harm. Consumption patterns and resource utilise are very loftier in some parts of the earth, while in others—frequently in countries with far more people—they are low, and the bones needs of whole populations are non being met. A written report undertaken in 2009 showed that the countries with the fastest population growth also had the slowest increases in carbon emissions. The reverse was also true—for example the population of North America grew just four per cent between 1980 and 2005, while its carbon emissions grew past 14 per cent.

Individuals living in developed countries have, in general, a much bigger ecological footprint than those living in the developing world. The ecological footprint is a standardised measure of how much productive land and water is needed to produce the resource that are consumed, and to absorb the wastes produced by a person or grouping of people.

Today humanity uses the equivalent of 1.5 planets to provide the resources we utilize and absorb our waste. This means it now takes the Globe one twelvemonth and 6 months to regenerate what nosotros use in a twelvemonth.Global Footprint Network

When Australian consumption is viewed from a global perspective, we leave an uncommonly large 'ecological footprint'—one of the largest in the world. While the boilerplate global footprint is ii.seven global hectares, in 2014 Australia's ecological footprint was calculated at six.7 global hectares per person (this large number is mostly due to our carbon emissions). To put this in perspective, if the rest of globe lived similar we practice in Australia, we would need the equivalent of iii.half-dozen Earths to meet the demand.

Similarly, an American has an ecological footprint almost nine times larger than an Indian—so while the population of India far exceeds that of the United states, in terms of environmental impairment, it is the American consumption of resources that is causing the higher level of damage to the planet.

What is the solution?

How do we solve the delicate problem of population growth and environmental limitations? Joel Cohen, a mathematician and author characterised potential solutions in the following mode:

1. A bigger pie: Technical innovation

This theory looks to innovation and engineering as Earth's saviour, not only to extend the planet's homo conveying capacity, but to too meliorate the quality of life for each private. Advances in food production technologies such equally agriculture, water purification and genetic applied science may help to feed the masses, while moving away from fossil fuels to renewable power sources such as wind and solar will go some way to reducing climatic change.

'Economical decoupling' refers to the power of an economic system to grow without corresponding increases in environmental pressure. In 2014 the United Nations Surroundings Programme (UNEP) released a report titled 'Decoupling two', which explored the possibilities and opportunities of engineering science and innovation to advance decoupling, and an analysis of how far technical innovation can go.

Funding and research should be a high priority in these areas, merely we must accept that applied science can simply do then much, and is just office of the solution.

two. Fewer forks: Teaching and policy change

This theory is based on demographic transition, finer finding ways to slow or stop population growth resulting in fewer people fighting for resources or 'slices' of pie.

Nativity rates naturally reject when populations are given access to sexual and reproductive healthcare, education for boys and girls beyond the principal level is encouraged and made bachelor, and women are empowered to participate in social and political life. Continuing to support programs and policies in these areas should run across a corresponding drop in birth rates. Similarly, as the incomes of individuals in developing countries increase, there is a corresponding decrease in nascency rates. This is another incentive for richer countries to help their poorer neighbours reach their evolution potential.

Providing a wellness, educational or financial incentive has also proven to be constructive in combating some population issues. For example, paying money to people with ii or fewer children or allowing gratis didactics for families with a single child has been trialled with some success. However, in that location are debates well-nigh incentive programs (such as paying women in India to undergo sterilisation). Opponents question whether accepting these incentives is really is a choice, or whether the recipient has been coerced into information technology through community pressure or fiscal agony.

Fewer forks tin also cover another complicated surface area—the option of seriously controlling population growth by force. Red china has done so in the past and attracted both high praise and severe humanitarian criticism. This is a morally-, economically- and politically-charged topic, to which there is no easy answer.

3. Better manners: Less is more

The improve manners approach seeks to educate people almost their actions and the consequences of those actions, leading to a alter in behaviour. This relates not but to individuals simply also governments. Individuals beyond the world, merely particularly in adult countries, need to reassess their consumption patterns. Numerous studies have shown that more 'stuff' doesn't brand people happier anyhow. Nosotros demand to footstep back and re-examine what is important and actively find ways to reduce the amount of resources we consume. Taking shorter showers, saying no to single-use plastics, buying less, recycling our waste product and reviewing our style and frequency of travel may seem picayune, just if millions around the world begin to do information technology likewise, the difference volition begin to add together up.

Governments also need to instigate shifts in environmental policy to protect and enhance natural areas, reduce COtwo and other greenhouse gas emissions, invest in renewable free energy sources and focus on conservation as priorities.

Developing countries should be supported by their more developed neighbours to attain their development goals in sustainable, practical ways.

In reality, there is no single, easy solution. All 3 options must exist part of a sustainable future.

Where to from hither?

Population is an issue that cannot exist ignored. While nosotros tin can all do our bit to reduce our own global footprint, the combined touch on of billions of other footprints will continue to add upward. In that location are many who believe that if we exercise non find ways of limiting the numbers of people on Earth ourselves, then Globe itself will somewhen discover ways of doing it for the states.

Interestingly, despite population increase being such a serious outcome, the United Nations has held only 3 globe conferences on population and evolution (in 1945, 1974 and 1994).

However, governments around the world are beginning to recognise the seriousness and importance of the state of affairs, and are taking steps to reduce the environmental impacts of increasing populations and consumption such as through pollution reduction targets for air, soil and h2o pollutants. The United Nations Climate change Conference in Paris, scheduled for December 2015, is ane instance; nevertheless any international policies demand to be backed upward past workable solutions at the individual, local and regional level.

Conclusion

With more than 7.3 billion people on the planet, it'southward easy to presume someone else will tackle and solve the outcome of population and environment. Yet information technology is an issue that affects u.s. all, and as such we're all responsible for working towards a sustainable futurity in which anybody is able to enjoy a good quality of life without destroying the very things we rely on to survive. It's possible, but it volition have the combined and coordinated efforts of individuals, communities, and governments to get there.

Source: https://www.science.org.au/curious/earth-environment/population-environment

0 Response to "What basic assumption about the environment did opponents to environmental regulation have?"

Post a Comment